Today I had a really transformative experience. My wife, Bùi Tuyết Minh, is the founder of Vietnam Dance Movement Therapy and helped to lead a workshop at the American Center in Hanoi for Vietnamese veterans who are suffering from cancer.

When I first heard that she was doing this workshop and that I would be lending musical accompaniment, I was intrigued, albeit a little apprehensive. I have collaborated so many times with my wife in tons of workshops, but this one in particular stood out to me. It seemed heavy and dark, but very important.

Here’s me, some American kid who had an easy life and grew up with very little connection to Vietnam or the Vietnam War. I knew my grandparents, father, and mother were against the war back in the day and that my dad once got arrested for throwing snowballs at cops at an antiwar protest while he was in college. The legend is that the cops shaved his head in jail and it never grew back.

Now my connection to Vietnam is much, much stronger as my wife is Vietnamese and daughter is both Vietnamese and American. I’ve lived in Vietnam for almost a year now and have learned about the rich cultural heritage of this country. In the USA, all I really knew of Vietnam was the war: seeing movies and reading books all from the American perspective. Though the Vietnam War was certainly not the defining factor of people and culture in Vietnam, it definitely was an extremely significant and traumatic event that has shaped lives of everyone in this country in some way.

The workshop began with the veterans and their wives talking about how they were affected by the war: what they did before, during, and after. Some were teachers, some were doctors, all called to fight and all profoundly affected by their time as soldiers. All of the conversation was in Vietnamese and though my Vietnamese has gotten better over the last year, I didn’t understand most of the words they were saying. Honestly, I didn’t really need to understand the words as I could understand the feeling, emotion, and pain in how they were talking.

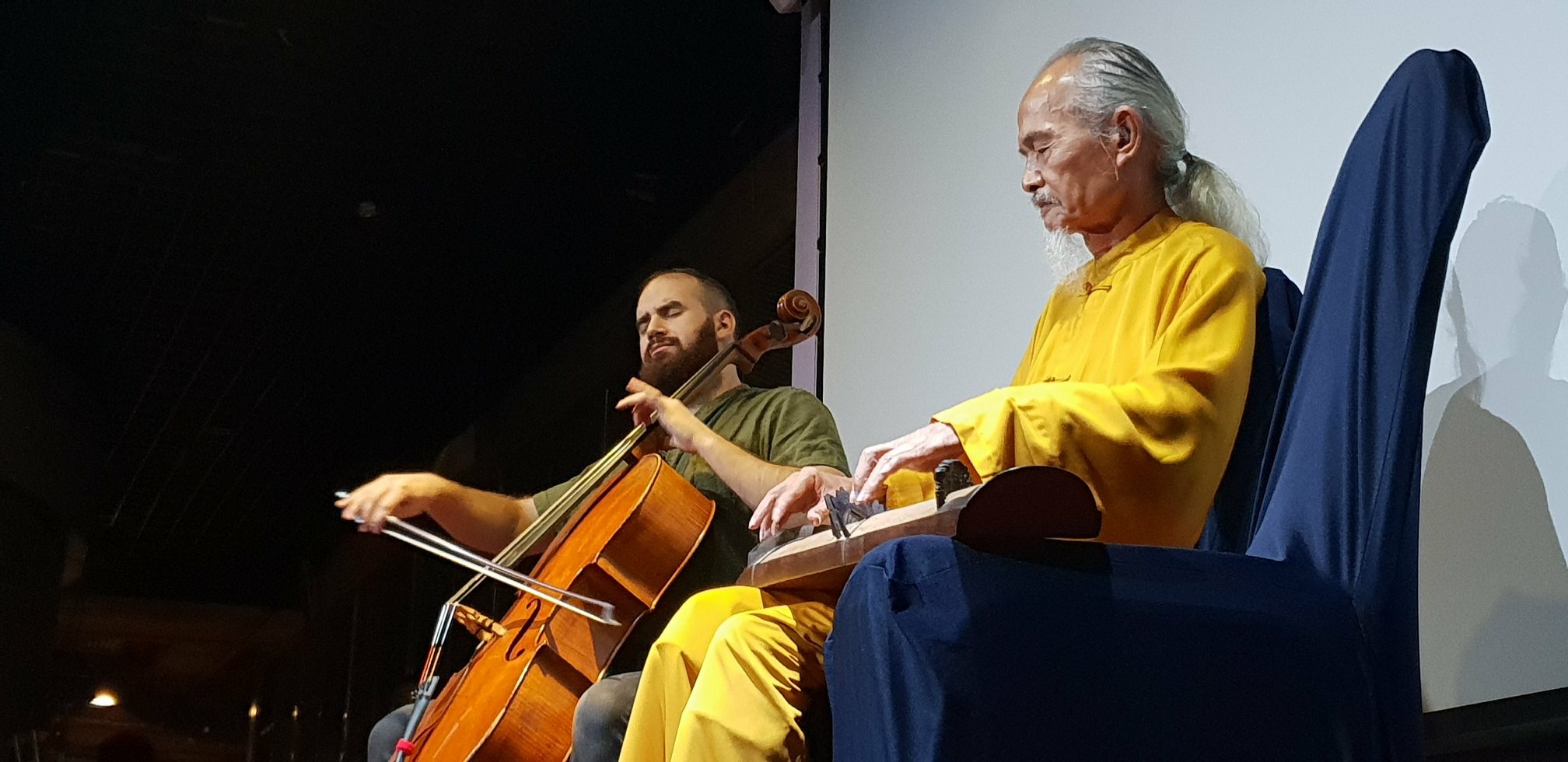

It’s funny, as someone who plays a very emotionally charged instrument and likes it for that fact, I really don’t like to talk about how I feel. After everyone had told their story at the beginning, Minh asked me if I wanted to say something. I really didn’t want to talk. I can be a good speaker and writer if I want to, but I just felt like it was so much easier in this situation to say what I wanted to say by playing. I played, Tinh Cha, a song for Vietnamese fathers and Minh began to facilitate the movements of the workshop.

You could see on their faces that the combination of the music and movement was really affecting them. It was quite powerful. Here was this music from their past, songs that they know and loved, recontextualized through the lens of some American man playing the cello.

This might sound pretentious, but despite the songs being familiar, I think what they were responding to is the intention and energy that I was giving the music. What I was trying to convey was a sense of healing, empathy, and compassion through my playing. I was trying in some ways to apologize for the stupid and often cruel things that countries do in the name of war, when at the end of the day, no matter what side you’re on, you’re still humans. No matter what side you are on when you see the horrors of war you are still a human being and you are going to be profoundly affected by this experience. What really separates you from the enemy? A uniform? A language?

It’s like that Thomas Hardy poem, “The Man He Killed.” It’s from the point of view of a soldier who killed an “enemy soldier,” and about how perhaps if they had met under different circumstances, they would have been friends. They would have had a drink at a bar and laughed. People aren’t governments. Governments get people involved in these conflicts, but it’s the people who suffer.

As I continued to play I could see the healing quality of what Minh and I were doing. I have to be honest, most times when I’m playing, I play for myself. The fact that people are sometimes deeply affected by my playing isn’t really my goal. I play because I enjoy playing and everything else that happens as a result is nice, but not my focus.

This was different. I wanted the audience to be touched in a positive way. I wanted them to see that though they may have seen some terrible things and now they are fighting for their lives from diseases inflicted by chemicals from the war, that every darkness has a light. Forty-four years after the end of the war I bet these men were not expecting to be at the American Center in Hanoi being played Vietnamese songs by an American cellist and being led in a dance workshop by his Vietnamese wife.

At the end of the session, the soldiers and their wives were very thankful for providing the workshop. I was thankful to them for giving me a chance and for sharing their deeply personal stories with us. I know I grew as a person, an artist, and human being. I hope I helped to give them some sort of relief and peace.

In an endlessly complicated and often scary world, never underestimate the healing power of music, dance, and the human connection. These are some of the few things that really matter in this world.